In the most general terms, an over-the-counter (OTC) product can be described as a medicine available for self-medication that does not require a doctor’s prescription. Self-medication is a common treatment of many routine health problems such as headaches, allergies, and skin conditions. OTC drugs are designed, labeled, and approved by various regulatory agencies around the world for use without medical supervision.

As more medications move to OTC status, people are interested in playing a more active role in managing their health and controlling their healthcare choices. As a result, OTC products are generally accepted as an important part of healthcare. However, self-medication comes with risks. The understanding of what constitutes an OTC drug and the mode of dispensing can differ widely between regions and countries.

How Do I Get OTC Products in the U.S.?

In the United States, non-prescription or OTC drug sale is not limited to pharmacies. Only in rare instances are U.S. OTC’s stored behind the counter and dispensed by registered pharmacists. These OTC drugs are often located on pharmacy shelves easily accessible to patients and may also be located in non-pharmacy outlets, such as groceries, convenience stores, and large discount retailers.

OTC drugs generally have the following characteristics:

- their benefits outweigh their risks

- the potential for misuse and abuse is low

- the consumer can use them for self-diagnosed conditions

- has adequate labeling approved by a regulatory agency

- Medical supervision is not needed for the safe and effective use of the product

More than 300,000 OTC drug products are marketed in the United States, containing about 800 significant active ingredients. These include more than 80 OTC drug classes or therapeutic categories, ranging from acne to weight control medications.

With escalating health care costs in the US, consumers spend several billions of dollars on OTC drugs for self-medicating per year. Therefore, it is essential for the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to take steps to ensure that the manufacturers of these products comply with the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (FD&C Act) and meet all the regulatory requirements.

How Do Companies Bring OTC Drugs to Market?

FDA's review of OTC drugs is primarily handled by the Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER)'s Office of Nonprescription Drugs. CDER oversees the development, review, and regulation of nonprescription products. OTC drugs are developed under either the OTC Monograph process or New Drug Application (NDA) process.

Originally, under the Food, Drug & Cosmetics (FD&C) Act, only those products that had been on the market for a “significant period of time” and “to a material extent” was considered for OTC status. In 1972, the FDA initiated an OTC Drug Products Review process to establish monographs and evaluate the safety and effectiveness of OTC drug products marketed in the U.S. at the time.

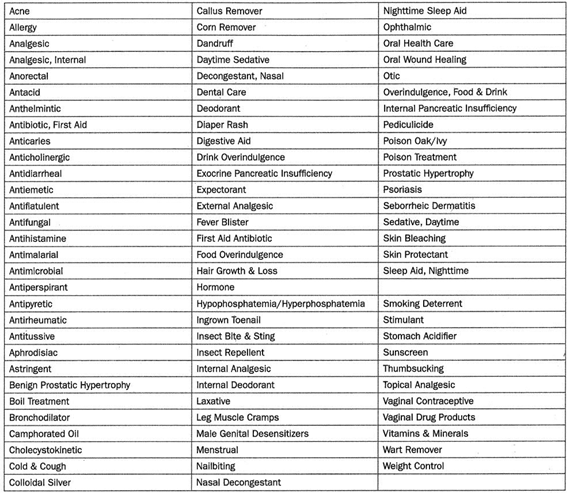

OTC drug monographs are a kind of "recipe book" covering acceptable ingredients, dosage strength, dosage form, formulation, and labeling (indications, warnings, and directions for use) necessary and appropriate for the safe and effective use of that drug. The FDA reviewed the active ingredients and labeling of more than 80 therapeutic categories of drugs rather than reviewing individual drug products (detailed in Table 1).

▲Table 1: OTC monograph therapeutic categories, ranging from acne drug products to weight control products

▲Table 1: OTC monograph therapeutic categories, ranging from acne drug products to weight control products

The FDA was able to make the process more efficient by grouping products into categories and evaluating active ingredients rather than each individual product. Following the review of each therapeutic category, an OTC monograph is developed and established as standards through the three-phase public rulemaking process:

-

call for information

-

proposed rules

-

codified final rule

Each phase requires a Federal Register publication, including in the form of an Advanced Notice of Proposed Rulemaking (ANPR), Tentative Final Monograph (TFM), and Final Monograph (FM) respectively.

According to the terms of review, the Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient(s) (API) in OTC products are categorizing into one of three categories:

-

Category I: generally recognized as safe and effective (GRASE) for the claimed therapeutic indication

-

Category II: not generally recognized as safe and effective (NGRASE) or unacceptable indications

-

Category III: insufficient data available to permit final classification

The Final Monograph establishes conditions under which certain OTC drug products are GRASE (Category I) and will further be codified in the Code of Federal Regulations (CFR) as a final rule. Drugs in compliance with appropriate monographs can be manufactured and marketed legally without FDA pre-approval. Most importantly, all OTC drug manufacturing activity must comply with Current Good Manufacturing Practices (CGMP) for pharmaceutical manufacturing. Drug substance and drug product manufacturing sites must be registered with FDA. In addition to registration, all OTC firms must formally list all of their drug products in commercial distribution in the United States with the FDA. The FDA has the authority to conduct inspections to verify the compliance of these manufacturing sites. OTC drug products also are required to be “listed;” the National Drug Code (NDC) is suggested, but not required, to be displayed on the product label.

The monograph process can be very lengthy, as the FDA timelines for moving a Tentative Final Monograph (TFM) to a Final Monograph (FM) have not been defined. Hence, several categories of drugs have not yet been subject to an FM. Once a category of products reaches FM status, the products classified as Category II are considered Non-monograph and must obtain approval by the New Drug Application process or be withdrawn from the market in a defined timeframe.

When a monograph has not been finalized, Category III products can remain on the market, but need to provide missing safety and/or efficacy data to be evaluated by FDA, which then may allow the ingredient to be moved to Category I.

After publication, a Final Monograph may be amended, either on the agency’s initiative or upon the petition of any “interested person.” OTC drug monographs are updated to add, change, or remove ingredients, labeling, or other pertinent information, as needed.

What Does the OTC “Drug Facts” Label Mean for Consumers?

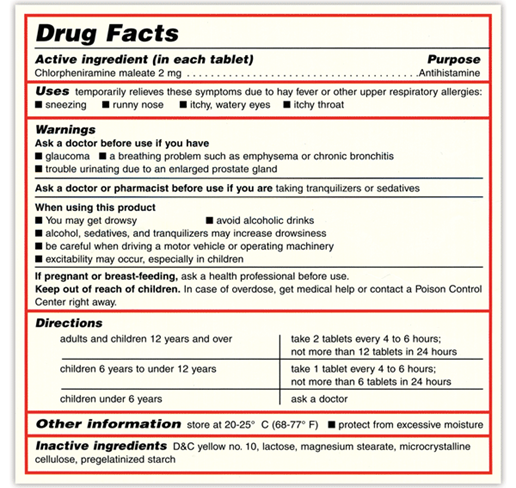

The fact that a drug is an OTC (non-prescription) rather than prescription does not mean it is risk-free. It is especially important for patients to understand that all drugs including OTCs, may have unwanted side effects. Aside from the benefits OTC medications offer, they can carry risks, including the possibility of unwanted side effects, drug or food interactions, or harm due to excessive doses. These risks are disclosed on the “Drug Facts” Label on all OTC products.

As with prescription drugs, the CDER oversees OTC drugs to ensure that they are properly labeled and that their benefits outweigh their risks. Previously, information about product instructions, warnings, and approved uses appeared in different places on the label depending on the OTC product and brand. Finding information about inactive ingredients has also been a challenge for those who may be allergic to any ingredient in a drug product. A final rule on the use of “Drug Facts” became effective in 1999, which standardized the format, content, headings, graphics, and minimum type size required for all OTC drug products. All OTC drug labels have detailed usage and warning information to help consumers determine whether the product is appropriate to treat their conditions and how to take the product correctly without a healthcare professional’s oversight.

▲Fig.1: An example of an OTC “Drug Facts” label

▲Fig.1: An example of an OTC “Drug Facts” label

As Fig. 1, specific information on the OTC Drug Facts label must include:

-

Active ingredient(s)

-

Purpose

-

Uses

-

Warnings

-

Directions

-

Other information

-

Inactive ingredients

-

Questions

All OTC drug products must bear the “Drug Facts” label using simple language and an easy-to-read format to help people compare and select OTC drugs at the time of purchase, and help the consumer understand and follow the product’s usage and safety information without medical supervision.

What are the Manufacturing Requirements for OTC Products?

The manufacturing of OTC products is identical to manufacturing prescription (Rx) products except for FDA approval for marketing and sales of these products.

FDA requires that all OTC establishments adhere to Current Good Manufacturing Practices (CGMP) and follow labeling requirements as specified in 21 CFR Part 201. In addition to the information that must appear on the label or immediate container, the Drug Facts Rule (published by the FDA in 1999) standardized the content requirements and format for the labeling of all OTC products. Drug Facts Rule labeling requires, among other things, a description of the active ingredients and their purpose, the products’ uses, warnings, directions, other information, and inactive ingredients.

FDA requirements for all OTC products include drug establishment registration, drug product listing, and adherence to GMP regulations. FDA requirements for OTC drugs vary for OTC monograph products and new OTC drugs. Drugs with active ingredients published in the OTC final monograph can be marketed without prior approval from FDA. However, if you are planning to market OTC drugs with active ingredients that are not part of the OTC monograph, you should obtain FDA approval through the new drug approval process. A list of OTC monograph ingredients along with FDA regulation for OTC drugs can be found in the 21 CFR Part 330.

What Are FDA’s Packaging Requirements for OTC Products?

FDA established a uniform national requirement for tamper-evident packaging of OTC drug products that improved the security of OTC drug packaging and helped assure the safety and effectiveness of OTC drug products. A tamper-evident package is having one or more indicators or barriers to entry which, if breached or missing, can reasonably be expected to provide visible evidence to consumers that tampering has occurred. Statements must be included on both outer and inner cartons clearly describing the tamper-evident features.

In addition, OTC drugs must comply with child-resistant packaging requirements in response to incidents of children opening household packaging and ingesting the contents. A provision is in place for one container size to be marketed in non-child-resistant packaging for elderly or handicapped persons unable to use the child-resistant packaging, as long as it is adequately labeled and child-resistant packages also are supplied.

The demand for OTC medications are increasing as governments seek to reduce healthcare costs, and patient’s healthcare expectations and interest is becoming more active in managing their health. It is the responsibility of both the pharmaceutical industry and regulatory authorities to raise public awareness of both the benefits and risks involved in using OTC medications for self-medication, so patients can use these medicines correctly and minimize the possibilities of drug misuse and abuse.

OTC drug manufacturers must comply with the same quality standards and regulatory requirements as those for prescription products. However, unlike prescription products, OTC products must be proven to be safe and effective for use without healthcare professional supervision. Several regulatory pathways are available to market OTC drugs in the US. Ensuring compliance with the applicable rules and regulations is essential in the dynamic and challenging arena of OTC drugs.

.png?width=626&name=TT%20CTA%20(3).png)